In a now offline interview from March 7th 2014, gamestm.com interviews Vijay Lakshman, the Game Director and Lead Designer of The Elder Scrolls Chapter I: Arena about his work originating the series...

Dragon shouts may be all the rage these days, but we talk to The Elder Scrolls co-creator to discover why you should always respect your elders. When you think of Western developed role-playing games, one of the first names that springs to mind is undoubtedly Bethesda.

This legendary game studio was founded in 1986 as Bethesda Softworks, and while its initial batch of sports titles were a tad pedestrian, it wasn’t long before it was developing games based on popular film licenses. This included the first officially licensed Terminator game and the NES version of Home Alone. Skip forward to the modern day and Bethesda Games Studio is best known for Fallout 3 and the ever popular The Elder Scrolls series. But just how did Bethesda go from being just another game studio to the role-playing master?

One man who knows better than most is the Lead Designer of the first Elder Scrolls game, Vijay Lakshman. “I’d recently accepted a position as an IT specialist at the American Banking Association when I got a call from Julian”, Lakshman explains when asked about how he first came to work for Bethesda Softworks alongside Julian Jensen, Lead Programmer on The Elder Scrolls: Arena. “It turns out that the résumé I had submitted a month earlier finally got to his desk, and he gave me a call. He asked if I would like to be a Producer. Having no idea what that was, I of course said, yes! The rest, shall we say, is history.”

The inaugural Elder Scrolls game would come soon after, but first Lakshman had to cut his teeth on something less D&D and more slam dunk. “My first project was NCAA: Road to the Final Four”, Lakshman recalls. “It was a project in need of extra hands as Julian was serving as the Producer, Designer and Technical Director. Way too much on one plate, yet he was handling it all. I think he got sick of 15 hour days and decided I might be of some use. After that, we worked on all of Bethesda’s games, including Wayne Gretzky Hockey and Terminator: 2029. Each was a learning experience in and of itself.”

One thing that stands out about The Elder Scrolls: Arena is the unusual subtitle. Where’s the sense in using “Arena” to describe a role-playing game that’s set across a whole continent? Simply put, the series didn’t begin life as a dungeon crawler, but rather an arena-based combat game where you managed a team of gladiators. “Julian and I loved RPGs, and in particular the stuff out of Origin”, Lakshman reminisces. “One day we were sitting outside and I pitched a game based loosely on the Rutger Hauer movie, Flesh and Blood. It was about a team of gladiators that travelled around the empire and fought for cash and fame.”

“We thought we could create an actual league based on the stuff we’d learned from Hockey League Simulator, but with real gladiators fighting”, Lakshman continues. “We thought it would be cool to hear about ‘Kretos the Dark’ off in Mournhold, and have to go recruit him. Combat would take place in pre-set dungeons and be akin to capture the flag, but with death possible. We spent a lot of time on the backstory and world, but had no plot. This was supposed to be a combat-centric game.” But in the end, the side-quests became more engaging than the original concept, and so the team ditched the gladiatorial focus.

Changing the game plan mid-development would be disastrous for a modern day monster like Oblivion or Skyrim, but with only a handful of people on the original development team, progress was comparatively easier to manage. “We were about eight to 10 awesome and overworked people that maybe grew to 12 at some point”, Lakshman reflects. “It was a very small team by today’s standards. Ted Peterson was an amazing designer who deserves credit, as do the rest of the people ‘in the trenches’. The atmosphere was also awesome. We hated working late, who doesn’t, but who’s going to complain when you’re working at a game company? I loved it.”

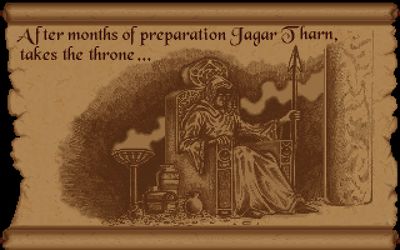

Despite being the inception point for one of the most iconic series in gaming, it’s safe to assume that most Skyrim players haven’t experienced Arena’s story first-hand. The game begins with The Emperor of Tamriel being imprisoned and then impersonated by an Imperial Battle Mage named Jager Tharn, and as a member of the Imperial Guard, it’s your job to thwart Jager’s plans by tracking down all eight pieces of the Staff of Chaos. Each one was hidden in a different providence of the Elder Scrolls world – including Morrowind and the Summerset Isle – and you had to talk to the right NPCs before discerning its location.

“Honestly, we were super late in development, and then management finally came in and said, you have to finish this and ship it”, Lakshman stresses. “We realized that we could bolt on a story, but the questing would be fairly linear. Remember, it was supposed to be a combat oriented game about gladiators, but AI was difficult, pathing was difficult and we still hadn’t solved some of the more interesting features we wanted to do like episodic content. So I spent a month and came up with the story. If you add up all the writing in the original Elder Scrolls, it was about five books worth!”

If the writing was dense enough to cover several novels, then the game world was large enough to fill a continent-sized map. Bethesda was never able to give an exact figure on just how large Arena was but the estimate is around six million square kilometres. That not only eclipses the 41 square kilometres of Skyrim, but it also made the fast travel system an absolute necessity. The reason for this geographical gulf is simple. The main towns and dungeons in Arena were manually designed, but once you ventured out into the wilderness of Tamriel, everything was procedurally generated.

“Originally, we didn’t expect people to play it like an RPG, but rather like a sports game”, Lakshman offers when asked about the randomised landscape. “So after a season you’d want to play again. The only way to do that was to procedurally generate the world and the gladiators, so that we could give each season a unique and fresh feel. The exploration part was relatively easy if you look at it from that angle. What does a gladiator want? Advantage in the next match. Where do you find it? On a random monster loot drop. What do you do? Look for random monsters. All in all, it held together well for how it was originally conceived as a combat game.”

The scope of Tamriel was one thing, but in terms of giving each province a distinct personality, the thing that really stood out was the eight playable races – which ranged from three human and three elf races to the more exotic Argonians and Khajiit. “I used to love the old Sinba movies and fondly recalled some of the stop-motion creatures they would fight”, Lakshman reflects. “For some reason, the word Argonian stuck with me (from Jason and the Argonauts) and I equated that to exploration. What’s at the farthest reach of your mind and the world? In my mind, there be dragons, hence the Argonians being reptilian.”

That explains the humanoid reptiles, but what about the less obvious nod to The Eye of Thundera? “With the Khajiit, I’d spent a lifetime as a practitioner of the martial arts”, Lakshman explains. “I’ve trained for 30 years, was a nationally ranked black belt and competed in over 1200 combats in the ring. I knew I wanted to make a feline race, and I saw their grace and agility as an intrinsic quality, much like a martial artist. In Japan, the art of the sword is called Kenjitsu. I modified that to become Khajiit, and thus the race of these highly nimble and agile felines was born!” And as the series progressed, the Khajiit became more cat-like in appearance.

The deep level of customisation that Arena offered was another way in which the game immersed players into its fantasy world. There were 18 in total, and these ranged from the standard Warrior that could wear enchanted plate armour and the Assassin that had the highest chance to land a critical hit, to more exotic classes like the difficult to hit Acrobat and the Nightblade that could pick locks and cast spells. But out of all the character classes that Lakshman and the team came up with, the most unorthodox was a mage that acted like a living battery.

The Sorcerer class was unique in that it couldn’t generate its own spell points automatically. Instead, you had to absorb enemy spells before you could start casting your own repertoire of magic. “I’m an avid reader”, Lakshman offers when asked about the Sorcerer’s inspiration. “I think I’ve read over 2000 fantasy and sci-fi novels to date. One of my favourites is Elric of Melnibone. He had a sword, Stormbringer, which would absorb the life force of his opponents and sometimes his friends. I wanted a class to become the Stormbringer of The Elder Scrolls world, and so I made the Sorcerer this living weapon.”

Speaking with Laksham, it’s clear that he and other members of the development team were fans of fantasy games and literature, and you only need to compare The Elder Scrolls mythology to older works like Warhammer Fantasy and even The Lord of the Rings to appreciate that a new fantasy world is invariably influenced by the ones that came before it. But when you consider the wealth of RPG staples that the team fused into every aspect of the game’s progression system – with everything from experience levels to customisable spells – it’s clear that Arena’s primary influence is the grandfather of the RPG itself.

“Anyone who says Dungeons & Dragons didn’t influence them didn’t play Dungeons & Dragons”, Lakshman states as a matter of fact. “I spent summer after summer with my friends ‘geeking’ out. We’d play Dungeons & Dragons, Aftermath, Paranoia (thanks Ken Rolston!), RuneQuest and pour over combat tables and sheets called Arms Law and Claw Law. The basis of The Elder Scrolls was a combination of what we thought worked and what we could implement. Luckily, Julian is sort of a statistical whiz, so he somehow managed to turn my non-mathematical ramblings into useful code.” You could almost call it a Carmack and Romero-style relationship.

While the original Elder Scrolls team may not have the same industry wide prestige of the Doom creators, what they set in motion less than a year later would become just as successful. And while a lot of that has to do with the timeless Morrowind that was led by Todd Howard, many elements of the revered sequels can be traced back to the humble original. “I remember sitting outside in the spring of 1993”, Lakshman recalls when asked about the high points of development. “I was figuring out how to create gladiators with real stats that you’d want to recruit, and then how you’d entice them to join you. That was definitely one of my fondest memories.”

As steady as the development was, the Arena team still encountered its fair share of speed bumps, one of which was a proposed Christmas 1993 release date that had to be pushed back to early 1994. “We hated missing it and I think everyone felt the pressure”, Lakshman acknowledges. “You have to remember that Bethesda was a small company back then, maybe 25 people. That said, management left Julian and me alone at the right time. We needed to think, to regroup and put together whatever we could once we knew we wouldn’t get all the parts of the gladiator game done. That took real thought and a lot of late nights.”

When the Arena finally made its way onto the shelves of videogame purveyors, complete with gladiatorial box-art that was completely at odds with its dungeon raiding gameplay, reports suggest it was somewhat buggy and initially sold as few as 3000 copies. “You always think you’re ready to launch”, Lakshman offers when asked about the initially slow uptake. “Back then we had small testing budgets and most of the testing was done by me and a small team of high school interns. It was both crazy and inspiring, that such a small team could’ve gotten so much done in a relatively short space of time.”

To make sure that all its hard work wouldn’t be overlooked, Bethesda released a number of patches in addition to a more stable Deluxe Edition that ironed out most of the bugs. “The Elder Scrolls was (and continues to be) a very complex system of statistical generation of appropriate events”, Lakshman challenges when we suggest that old habits die hard. “This kind of game is difficult to test because you simply cannot duplicate every test instance. That being said, this system gives you an open-ended world and allows a player to play infinitely. I think the trade-off has proven to be acceptable by the fans.”

Considering the series has amassed over 25 million sales to date, we have to agree, and when Lakshman described how far the team went to see the game shipped, our respect was cemented further. “We had a great team of hardworking developers who truly put in their best effort”, Lakshman stresses. “No one wore only one hat, and we were all familiar with what everyone did. We even spent time shrink wrapping the games ourselves, as Bethesda was the publisher and developer. We were in the loading dock and we learned how to assemble boxes, inserts and use the heat gun. Talk about seeing a product through from concept to box wrap! We did it all.”

While Lakshman and the team saw The Elder Scrolls: Arena through to completion, Bethesda would ultimately turn the series into a chart topping success. “I love them”, Lakshman exclaims when asked about the modern Elder Scrolls game. “The folks at Bethesda kept the franchise alive, poured their resources into it and turned it into a winner. They deserve it. I’m proud that my team could’ve done so much with so little, but I’m really awed at how much more complex the storylines, technology and adventures have grown, and how artfully woven the franchise has become. I take my hat off to the entire team at Bethesda today.”

It’s a classy way to end an enlightening discussion about a truly ambitious game. Today, Lakshman and Jensen work on educational software at Naaya, LLC – a studio that, unlike their former employer, is still based in the town of Bethesda in Maryland. And in a move that will surprise no one, Laksham has just published his first novel, Mythborn. The story follows the last seven days of a young apprentice assassin’s life. Whatever the success of his novel, though, Laksham can always claim to have started something that holds dear to so many. As far as achievements go, that’s a hard one to top.